Portrait photo courtesy of Habibeh Madjabadi.

Middle East

Iran

Tehran

Habibeh Madjabadi, born in 1977, is a prominent Iranian architect whose work has received extensive recognition from local and international media.

Her exploratory approach transcends traditional architectural boundaries, allowing her to make significant contributions to conceptual art and design.

Madjdabadi is known for her innovative ideas that emphasise the role of culture and geographical context in her designs. She pays close attention to material selection and fabrication methods, viewing materials as vital means of expression. She approaches materials from a poetic perspective in her work, uncovering their natural qualities and interactions with the human body through artisan methods.

She began her professional career in 2003 by establishing her design studio in Tehran, shortly after winning first prize in a design competition for restoring a significant historical building in Iran. Since then, she has received several awards and recognitions, including being shortlisted for the Aga Khan Award in 2016.

Madjdabadi has held numerous lectures worldwide, including Italy, Austria, Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, Bosnia, Albania, Cyprus, Slovakia, Hungary, India, and Turkey. Her work has been exhibited at prestigious venues such as the Venice Biennale, TU Wien University, and Melbourne University.

The Overarching Commitment

The Blurred Boundaries Of Virtual Ties

As an Iranian, I reflect on how Iran has been largely closed off to the world for a long time—few tourists and limited travel abroad for Iranians. Before the internet, this isolation was even more pronounced; there was little connection or communication, and other countries knew very little about what was happening in Iran. However, with the internet, the geographical borders have blurred and almost disappeared, allowing for more interaction.

Personally, I have embraced the fact that part of my work now involves travelling, even though I am not particularly fond of giving presentations or talks. Yet, I have accepted that this is part of the job. After all, most of us architects would prefer to sit quietly in our offices, drawing and designing. But it has become a natural and essential part of my life now, as it gives me the chance to speak about what is happening in Iran’s architectural scene.

The House of Approximiation by Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio. Photo courtesy of Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio.

The Slower You Go

The Faster You Get There

Contemporary Iranian Architecture

Defining Progress

The Challenges

Before the 1973 revolution in Iran, there were a few exceptional and renowned architects who created large-scale public projects. Architects like Kamran Diba, Aziz Farmanfarmayan, Nader Ardalan, and Javad Hatami contributed to the architecture scene with their significant works. However, after the revolution, the landscape for architecture changed drastically.

In the 1980s, during the Iran-Iraq war and the "cultural revolution", architecture was seen as a luxury. Universities were shut down for some time, and once they reopened, the focus was on survival and rebuilding rather than architectural development. People questioned the need for architecture during the war, and the profession faded from public attention.

A well-constructed building does not always meet the criteria for distinguished architecture. Although, it is still a "good" building.

Gradually In the past 30 years, with the efforts of the new generation of architects, architecture has gained a respected position in Iran. It is now seen not only as a technical field but also as an art form, holding cultural significance. Architects in Iran are held in high esteem and regarded as creators who balance engineering with artistic vision.

Today, many contemporary, design-led architects in Iran are gaining recognition worldwide. By following international design awards and publications, one can see an increasing number of successful projects from Iran being published and celebrated.

What makes these projects stand out is their depth and narrative. Iranian architecture often delves deeper into the essence of architecture itself. While projects from other countries may be more advanced in terms of engineering and sustainability—with higher construction standards—I have come to realise that a well-constructed building does not always meet the criteria for distinguished architecture, although it is still a good “building".

In Iran, although we may lack buildings with the most cutting-edge construction standards, we have an abundance of architectural works that are considered pieces of art. The richness of Iranian architecture lies in its ability to transcend mere functionality, offering a deeper, more meaningful experience.

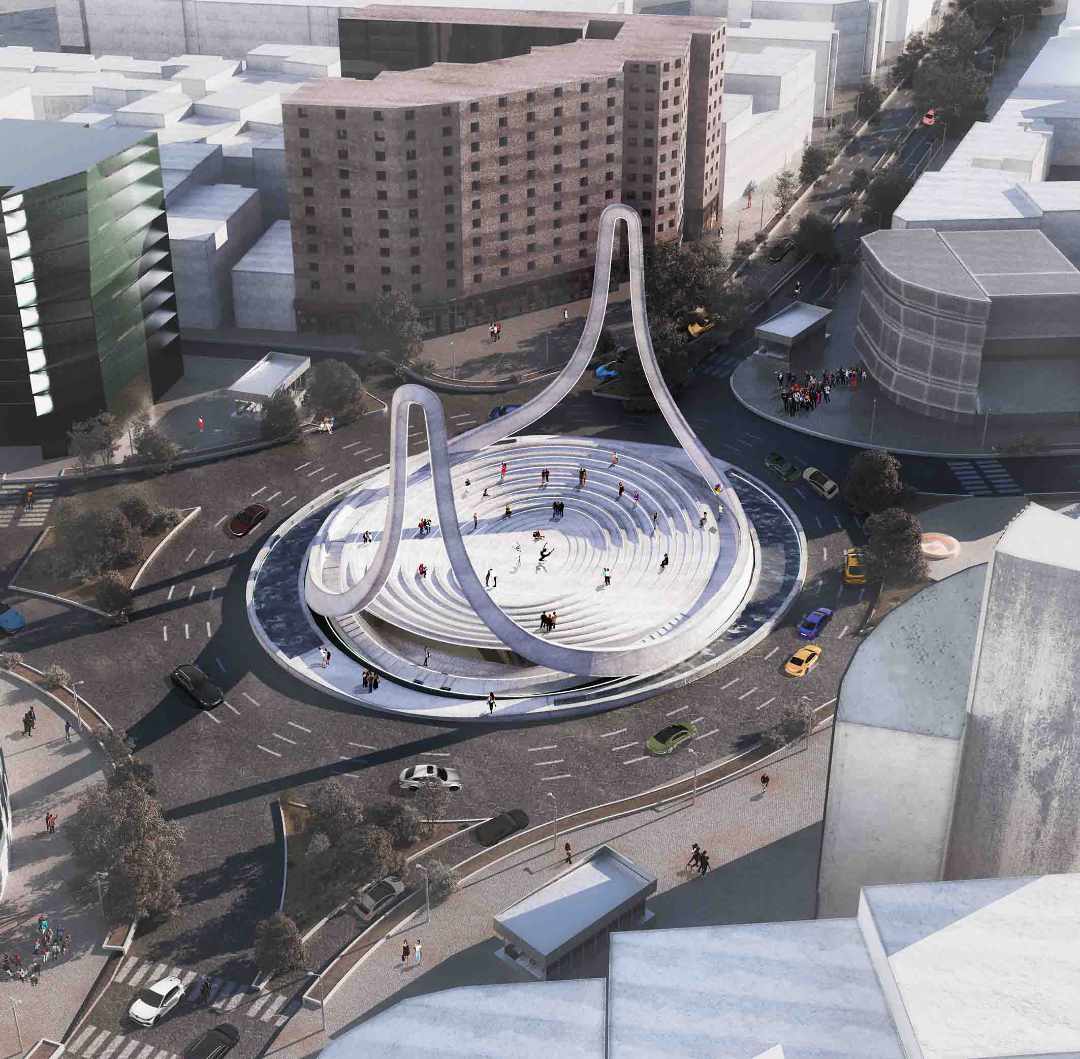

Winning proposal for the Vali-Asr Sqaure in Tehran, by Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio. Image courtesy of Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio.

Unfortunately, the realm of public architecture remains a different world. Despite the presence of talented architects, public projects are rare. Few public buildings have been constructed in recent years. Even when competitions are held, like the one for Vali Asr Square—a key part of the people’s collective narrative and history—there is little will to follow through.

Although our concept for a public square and gathering space won the competition, the authorities did not support it despite independent judges selecting it.

Public projects—mosques, museums, squares—are where architects can truly shape the life of a city.

The government’s lack of engagement with the profession motivates us to turn to the private sector. We find clients who are not only interested in art and culture but also recognise the financial value that good architecture can bring to real estate investments. Yet, this collaboration remains within a limited circle of like-minded clients and architects, resulting in a small number of architecturally precious projects.

I believe that today, the age of "starchitects" and branding has passed—what truly matters now are those who shape global architectural culture, even through more minor projects. These small projects, though modest in scale, hold immense potential for impact.

Perhaps the reason Iran has produced so many great contemporary architects in recent years is rooted in the very challenges we face. The restrictions and limits we work within, combined with our rich Persian heritage of art and architecture, have pushed us to rise to the occasion, resulting in more profound and resilient works of architecture. We hope to contribute, even in small ways, to the global culture of architecture.

I believe that today, the age of "starchitects" and branding has passed—what truly matters now are those who shape global architectural culture, even through more minor projects. These small projects, though modest in scale, hold immense potential for impact.

Progress is not always working towards a point in the future, but it can be working towards filling the forgotten gaps in our past.

I do not think that progress is linear. Sometimes, as we rush towards a goal, things are left behind. Progress is more like a dashed line—we must look back, identify the gaps, and work on them. Progress is not always working towards a point in the future, but it can be working towards filling the forgotten gaps in our past. We can find meaning by highlighting and addressing what has been forgotten.

Fortunately, Iran's rich Persian heritage provides resources for a contemporary voice that draws inspiration from the past without replicating it. This approach allows us to create architecture that connects tradition with the modern world, offering something both tangible and relevant today.

The Construction Industry

The Local And The Regional Appetite

Iran's unique circumstances set it apart from much of the world, and this distinction shapes how architects work and practice. Despite many challenges, the architectural field never comes to a standstill, mainly due to the country’s economic climate.

With high inflation, people rush to turn their money into assets to avoid devaluation—holding cash in the bank only leads to loss. Since the stock market is unreliable, construction becomes the safest investment.

Buildings in Iran often are treated as an object of value rather than a response to housing needs. Although there are 88.5 million people in the country, many of whom require homes, the construction boom is not driven solely by a housing shortage. Instead, inflation drives up property prices, and architectural quality can further boost value.

Interestingly, I noticed that real estate prices in Tehran were higher than in cities like Nice, France. Unlike in other countries where property value increases at a slower pace and is offset by upkeep and maintenance, in Iran, it is almost certain that a property purchased this year will significantly rise in price by the next.

One reason our business remains active is the nature of our investors and developers, who, unfortunately, lack cultural interests or hobbies.

Here, those with financial capacity primarily invest in residential buildings, holding onto them until prices rise before reselling. There is plenty of investment in smaller residential and office sectors but not in museums or cultural projects. Since these are not easily flipped for profit, there is no interest.

Ideally, governments are responsible for funding public projects, but when that does not happen, the private sector's intervention would be incredible.

While Iran shares a geographical region with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, the approach to progress and development between our governments has been starkly different.

As an Iranian architect with some international recognition, I have noticed that countries in the region are generally more inclined to work with iconic architects from the West. In general, there seems to be an interest in iconic figures as symbols of prestige. However, this might change in the future.

Globalisation Or Glocalisation

Embracing The Locality

Meaningful Work

Avoiding Replication

One of my main interests and areas of focus is how, as architects, we can be global while being local. How can we return to our cultural values while growing and introducing them globally? In my opinion, the path to becoming global starts with being local.

If an international architect simply replicates the same building systems elsewhere, it loses its appeal. For instance, when I visit India, I yearn to see what Indian architects are genuinely producing. If their work mirrors what is done in the US or Europe, it loses its appeal and fails to spark meaningful discussions among architects.

The path to becoming global starts with being local.

Being local in our design approach plays a significant role. By emphasising and celebrating the uniqueness of each place, we can showcase how, in Iran for example, we create architecture that is distinctly ours—something that simply cannot be replicated elsewhere in the world. This is what makes the work compelling and special.

Many Iranian architects, often unconsciously, favour modern technology over the rich culture of handmade craft in Iran, believing it to be superior. Even though technology can often be more expensive than traditional handmade techniques, they favour machine-made solutions, sometimes resulting in projects that - despite trying very hard - fall short of the technological achievement compared to those constructed in the West.

Even when handwork is necessary, there is a tendency to demand perfection, striving for a flawless finish that resembles machine production.

But why should we impose such standards on handmade creations? Just like a handmade rug, which may contain imperfections that actually raise its value, why should we attempt to disguise a handcrafted piece as if it were machine-made?

Crafting the facade elements of The House of Approximiation, by Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio. Photo courtesy of Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio.

These opportunities allow Iranian architects to step on paths many European architects may never have the chance to tread.

Instead, we often find ourselves walking down paths that reduce our work to mere reflections of projects built elsewhere, stripping our creations of their unique charm and identity.

Embracing our local context would not only enrich our practice but also enhance the architectural dialogue on a global scale.

Working Internationally

Share Architects

Experimental Architecture

Regarding our recent international collaboration, we have embarked on an exciting project initiated by Shared Architects. Thirteen architects from different countries are invited to create unique houses on a shared site. Each house manifests its architect's vision.

This project is located at Voronet Park in Romania, overseen by Shared Architects. The site is culturally rich, featuring a historic monastery and offering a stunning landscape. It serves as a platform for architects from diverse backgrounds to bring their ideas to life and experiment with new concepts.

We develop the initial concept and phase one while local architects adapt our designs to meet regional building regulations and codes. This ongoing collaboration ensures that our original ideas remain intact during the adaptation process.

A concept for a school in Mozambique; "when sustainability suggests a new kind of aesthetics", by Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio. Image courtesy of Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio.

These projects are indeed attractive, but they do not address the pressing housing crisis; instead, they serve as experimental initiatives. Similar to medicine, some doctors prescribe established medications that have proven effective over the years, while others work in laboratories, experimenting with new medicines. The architecture mirrors this distinction; some architects focus on developing projects based on proven systems and methods to tackle the housing crisis, as we cannot afford to wait for the outcomes of experimental endeavours, which may take considerable time to materialise.

Architects like myself operate in the "laboratories" of architecture, testing and blending ideas to potentially yield results that can inform future projects in different contexts.

The architectural landscape in Iran reflects this duality. Some developments occur without the involvement of design-focused architects, adhering to traditional standards and selling these properties to those who buy and inhabit them. Meanwhile, we continue our work in the laboratories, exploring innovative solutions and challenging the status quo.

‘Khassiat’

An Abstract, Shapeless Quality That Answers the ‘Why’ Behind a Design

In a TED Talk, Thomas Heatherwick argues that what often goes overlooked is the function of our feelings. Architecture should encompass this emotional dimension—the intangible aspects that shape our experiences. The adage "form follows function" can sometimes be misleading, as it tends to focus solely on physical functionality.

My concept of ‘khassiat’, addresses the underlying reasons behind a project’s creation. ‘Khassiat is a Persian word. I searched for a suitable English translation for the word "khassiat" for quite some time but couldn’t find anything that fully captures its meaning. While it could be loosely translated as “substance”, “potentiality” or “characteristic,” neither conveys the full essence of ‘khassiat.’

Therefore I decided that while most of the architectural terminology used globally comes from Western countries, this time, I aim to coin the term ‘khassiat’, which comes from the East.

In Farsi (Persian), a saying describes someone as lacking ‘khassiat.’ This person may be wholly able-bodied and function normally, but they are referred to as ‘bi-khassiat’, meaning “without essence”. This implies they lack that special quality or something unique that defines them.

For example, when discussing food in Farsi (Persian), a dish may look and taste good—because ‘khassiat’ is not solely about aesthetics or function—but it could still be considered ‘bi-khassiat’ if it lacks nutritional value.

It also can be true In medicine, the active ingredient has the ‘khassiat’ to cure a disease.

Similarly, in architecture, ‘khassiat’ represents that vital active ingredient. Some projects may have all the right components—an effective building system, high-quality materials, recognised beauty, and functionality—but when you see the building, you might still ask yourself, "What is its purpose, and why does it exist?" It lacks that essence.

As architects, we should actively seek out ‘khassiat’—the element that imparts soul and significance to the structure. Without it, a building is merely a shell, a lifeless entity. It is the ‘khassiat’ that infuses a space with meaning and vibrancy.

We should ask, what is the ‘khassiat’ behind this project? What does it truly address, and why? This term is rarely used in Iranian architectural discourse.

'Khassiat' is the starting point of a project. It is a quality that has no shape or form. At the beginning of the project, the architect makes an educated guess and decides that the project should achieve a certain level of 'khassiat'.

Khassiat is the starting point of a project. It is a quality that has no shape or form. At the beginning of the project, the architect makes an educated guess and decides that the project should achieve a certain level of 'khassiat'.

I begin my architecture process with the concept of ‘khassiat’.

In our project, The House of Approximation, the ‘khassiat’ focuses on achieving a specific percentage of complexity and approximation that elicits feelings of comfort and calmness in humans. Given that our ancestors lived in savannas, scientists have identified a particular level of complexity that is most suitable for human well-being. This may explain why modern minimalist architecture often becomes boring quickly; it raises the question of what makes it uninteresting, and one key factor is the level of complexity involved.

Thus, one of the aspects of ‘khassiat’ is an intangible quality that guides you toward this objective. As you follow this process, you may not know precisely what the final form will be or how it will manifest. Still, it will ultimately lead you to the specific ‘khassiat’ that resonates with the human experience.

For our project, the Lunar Complex—a multi-purpose service station along a highway designed for rest and shopping—I envisioned the ‘khassiat’ as a space where people could ascend the building, akin to a bridge that harmonises with the local landscape. This would allow visitors to enjoy the scenery and capture memorable photographs, enticing them to stop their cars and explore the area, whether to shop or simply relax and appreciate the view.

Proposal for The Lunar Complex—a multi-purpose Service Station, by Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio. Image courtesy of Habibeh Madjabadi Architecture Studio.

With this ‘khassiat’ in mind, I was guided through the design process to create a sweeping curve that extends to the ground, inviting people to climb up.

Initially, I did not focus on the specific form or curve; instead, I emphasised achieving that particular ‘khassiat’ of walking up the building. There are many ways to direct visitors upward and various potential forms, but the essential goal remains: to arrive at that experience of ascending the structure.

Starting with form can confine our creativity from the outset, but beginning with ‘khassiat’ opens up infinite possibilities and approaches.

Starting with form can confine our creativity from the outset, but beginning with ‘khassiat’ opens up infinite possibilities and approaches. This perspective allows anyone to engage with the project in their own way, exploring and interpreting that specific ‘khassiat’. Ultimately, it provides a meaningful response to the question of "so what?"—encouraging deeper connections and understanding of the architecture's significance.

September 2024

Interview by International Architects Sweden.